En atención a la creciente preocupación sobre la confianza en...

Leer más

Covid-19 challenge trial results are (finally) in: Here’s what should happen next

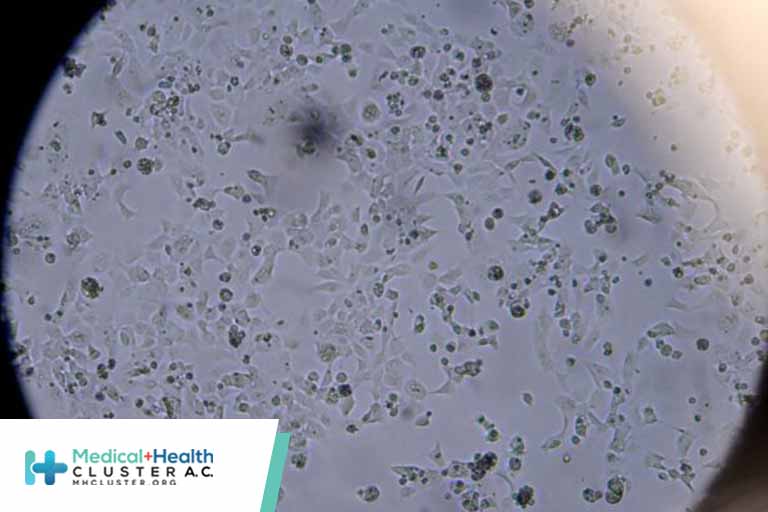

Results from the world’s first Covid-19 challenge trial are (finally) in: In the study, which was conducted by Imperial College London and hVIVO at the Royal Free Hospital in London, each of the 36 participants had drops of fluid containing a tiny amount of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, placed in their nostrils. Eighteen became infected, as confirmed by PCR testing, 16 of whom showed symptoms. The data, published in a preprint that has not yet been peer-reviewed, showed intriguing aspects of the virus’ progression, and all 36 participants finished the study healthy.

Why would anyone volunteer to be intentionally infected with SARS-CoV-2? It’s not as crazy as it sounds.

This trial is one of a long line of challenge trials in which volunteers sign up to receive a known pathogen. Such trials have been essential in developing vaccines for malaria, typhoid, and cholera and have established key facts about influenza, yellow fever, and the common cold.

By closely observing human infection in a controlled experiment from the moment of exposure onward, these studies can provide important insights that are difficult to obtain otherwise. They can also provide early signals of efficacy for vaccines and treatments.

Scientists have proposed challenge studies as essential for vaccine development for tuberculosis, hepatitis C, and group A Streptococcus. My organization, 1Day Sooner, represents challenge volunteers who want to participate in these studies, and several of our members were among the 36 participants given SARS-CoV-2

The fact the trial happened at all was an incredible accomplishment, and the British government deserves credit for its bold commitment to science as the only country yet to conduct such a challenge trial for Covid-19. If used properly, this research could create an important tool in Covid-19 research for testing intranasal vaccines, a universal coronavirus vaccine, and new antiviral therapies.

Anthony Fauci, director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has endorsed the use of challenge studies with common cold coronaviruses to develop urgently needed universal vaccines that can protect against new Covid strains and provide durable protection against Covid and similar viruses over the long-term. A wide range of coronavirus challenges can elucidate how effective immune responses to coronavirus infection work (a so-called correlate of protection) and help approve vaccines that are broadly protective, since protecting against common colds from the same genus as SARS-CoV-1 and -2 implies it will be difficult for viruses to mutate to evade protection.

But even though the use of Covid-19 challenges is now established, and effective treatments for Covid-19 make these trials safer than ever, there is no guarantee they will be effectively used.

The story of Covid-19 challenge trials has, so far, been too little too late. The idea of challenge trials was proposed in March of 2020, but it was only a year later that the Imperial College study was approved by an ethics committee. A paper with early results was submitted to a leading medical journal this past summer, but it was rejected and data from the study was not released until last week.

Had the data been published in the summer of 2021, the information offered about the validity of rapid tests could have been invaluable for public health guidance and diagnostic development. Now it merely confirms what we already know.

While my organization, 1Day Sooner, had no role in running the study, we have publicly called for greater transparency and urged earlier release of the results. But excess caution and the political obsession with avoiding controversy has stifled these studies and threatens their use for the future.

I congratulate the trial team for its hard work and important contributions to science. But it’s time to take this work, and what I hope is more like it, to the next level.

As researchers, pharmaceutical companies, governments, and funders look ahead to developing the next generation of vaccines with the urgency of the first wave, they need to properly fund work on universal and intranasal coronavirus vaccines and test them in challenge trials with old and new viral strains, including the Delta and Omicron strains of SARS-CoV-2 and similar viruses that cause the common cold.

Without new vaccines, the nature of waning Covid immunity means that annual boosters may well be required. Only half of Americans get their yearly flu shot, and in a country like the U.S. with significant vaccine hesitancy, there is a limit to what annual vaccination campaigns can accomplish. Moreover, regular boosters eat into the scarce supply and are simply not a viable option for most lower-income countries.

An important solution is longer-acting vaccines that ideally protect against a wide variety of SARS-like betacoronaviruses (called sarbecoviruses) and reduce transmission by inducing durable mucosal immunity, potentially by delivery as a nasal spray. Covid-19 challenge studies (and launching an Operation Warp Speed 2.0 to guarantee large purchases of effective universal vaccines) can help us get there.

As the full force of the pandemic became apparent, 1Day Sooner saw a boom in the number of people who wanted to volunteer for challenge and other studies. Unfortunately, our calls for urgency were not heeded. Business as usual, with the usual bureaucratic, regulatory, and research ethics committee hurdles, was the order of the day. The results of the first challenge trial offer the promise that a better world is possible, one where research participants can organize together, be heeded by scientists, and make their own choices to take risks to benefit society. I hope that promise can be fulfilled.

Créditos: Comité científico Covid